Behind the science:

Conventional and technical diving surveys reveal elevated biomass a...

2018, July 11

Posted by Veronica Radice

Fields

Community structure

Focusgroups

Fishes

Overall benthic (groups)

Locations

USA - Gulf of Mexico

Platforms

SCUBA (open-circuit or unspecified)

SCUBA (open-circuit or unspecified)

“Fish biomass and community composition in shallow and mesophotic coral reefs of Flower Garden Banks”

What was the most challenging aspect of your study (can be anything from field, lab to analysis)?

The most challenging aspect of this particular study was the boat ride through heavy seas to access the study sites. In my nearly 25 years of working in the field at sea, the transit ranks as one of my worst boat experiences. We had departed the dock in the evening and were scheduled to arrive on site the following morning, but as I remember it, quickly encountered inclement weather. I was in an upper, forward bunk, trying to sleep so that I would be well rested for diving operations the next day, yet the boat was pounded by waves for hours and hours. For what seemed all night long, I desperately attempted to wedge myself in my bunk to keep from being thrown out of it, while periodically being thrown into the roof of my bunk as the boat fell into the troughs of waves. The Flower Garden Banks, a US National Marine Sanctuary (FGBNMS) in the Gulf of Mexico has a reputation as a beautiful location and I was excited to see it firsthand, but as the night wore on, I was getting worried that I would be exhausted and in no shape to dive once we finally arrived. The smells and sounds of vomit were thick in the cabin and I’m still amazed I didn’t succumb to sea sickness, or fall out of my bunk. The diving made it all worth it, however, as the visibility, high coral coverage, and fish communities were outstanding!

What was the most memorable moment in undertaking this study?

This would have to be my first encounter with a tiger shark. I had previously encountered a variety of sharks while working but Galeocerdo cuvier always seemed to have a menacing reputation to me, and I had never encountered one underwater. On what was the last decompression stop of our dive, I was hovering at approximately 6 m water depth with five other people. The remote location of FGBNMS means that underwater visibility can often be very good and exceed 15 m. While waiting, I noticed a large school of rainbow runners (Elagatis bipinnulata) emerging from the depths, and I’d spent enough time underwater to know that very large fish are often encountered by a school of smaller attendant fish, that almost seem to announce their presence. Sure enough, as I began to see the end of the school of rainbow runners, a sizable (~3.5 m long, large enough to get one’s attention; estimated underwater and corroborated by others that observed the encounter on our waiting support boat) female tiger shark slowly followed her attendants and approached our party for a better view. She circled our group at close range before returning to the depths. She was a beautiful fish and what made the encounter so memorable was the excellent visibility allowed me to see her approach well in advance, her movements were curious and completely non-threatening, and I believe the other divers present made us all comfortable with this very close encounter with such a large animal.

What was your favorite research site in this study and why?

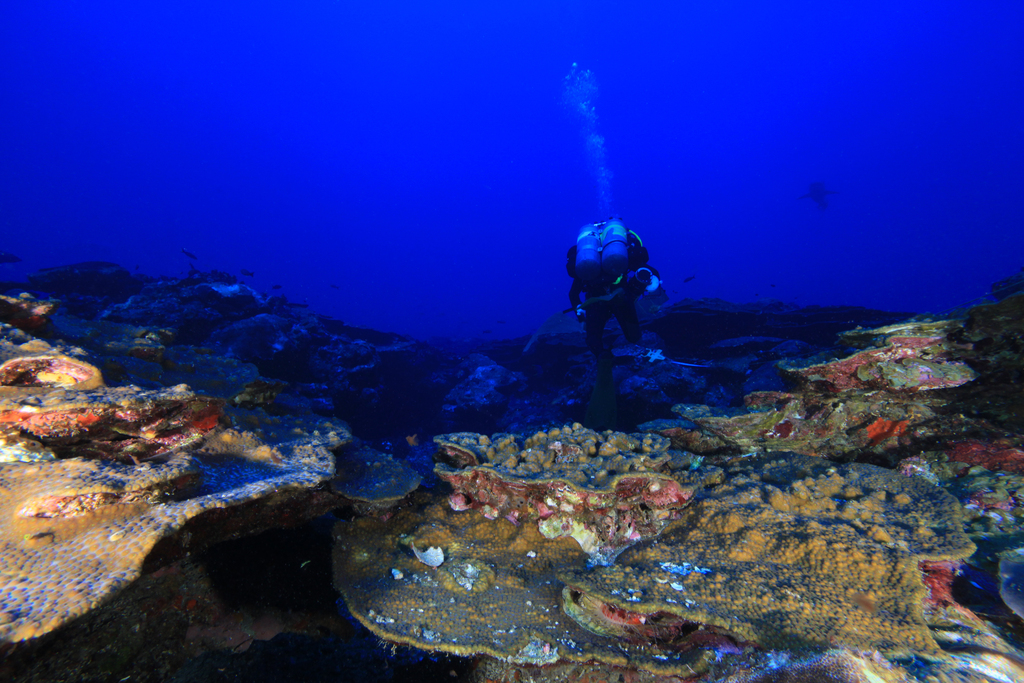

There are many beautiful dives at FGBNMS that are often associated with relatively high coral cover, clear water, and a vibrant fish community, so it’s hard to pick out a single best site. However, the abundance of large predators such as yellowmouth grouper (Mycteroperca interstitialis), marbled grouper (Dermatolepis inermis), and dog snapper (Lutjanus jocu) that our team encountered in upper mesophotic sites stands out. We sampled the fish community with underwater visual census transects of a predetermined length and width that we utilized to estimate the density of fishes that we encountered. Often, large transient animals like sharks, manta rays, or sea turtles might be observed in the water column or on a particular dive site but not necessarily within our sampling transect. On one site, however, a tiger shark actually cruised through my transect and I was lucky enough to have that encounter recorded by a member of our dive team (see photo).

Other than your co-authors, with whom would you like to share credit for this work?

The crews of the NOAA ship Nancy Foster and RV Manta, staff at FGBNMS, and an army of divers and support staff were instrumental to allowing us to access the remote location and safely conduct technical diving operations. These include L. Arbuckle, L. Bauer, K. Buch, E. Ebert, R. Eckert, K. Edwards, J. Embesi, D. Field, S. Henry, Z. Hileman, M. Johnston, D. Kesling, R. Mays, G. McFall, M. Nuttall, M. Ruiz, W. Sautter, G. Schmahl, M. Tartt, T. Tysall, A. Uhrin, J. Vander Pluym, J. Voss, J. Waddell, and M. Winfield.

Any important lessons learned (through mistakes, experience or methodological advances)?

As the first diver-based study comparing shallow with upper mesophotic fish communities and benthic habitats of FGBNMS, our work revealed similarities as well as distinct differences between these depth zones. The incorporation of technical diving was instrumental in allowing the sanctuary to better characterize living marine resources of the upper mesophotic, including the documentation of greater overall fish (as well as apex predator) biomass in the upper mesophotic, differences in apex predator community composition, and habitat differences between depth zones.

Can we expect any follow-up on this work?

Although some discussions of follow-up work have taken place, I don’t specifically have follow-up work currently planned. However, study sites at FGBNMS are part of the US National Coral Reef Monitoring Program and the marine sanctuary designation means that future monitoring and research at FGBNMS will remain a possibility as sanctuary management and science needs evolve.

Featured article:

|

|

Conventional and technical diving surveys reveal elevated biomass and differing fish community composition from shallow and upper mesophotic zones ... | article Muñoz RC, Buckel CA, Whitfield PE, Viehman S, Clark R, Taylor JC, Degan BP, Hickerson EL (2017) PLoS ONE 12:e0188598 |

|