Behind the science:

Spatial variability in reef‐fish assemblages in shallow and upper m...

2020, May 13

Posted by Veronica Radice

“Fish species assemblages in the Philippines relates to benthic condition across depth”

What was the most challenging aspect of your study (can be anything from field, lab to analysis)?

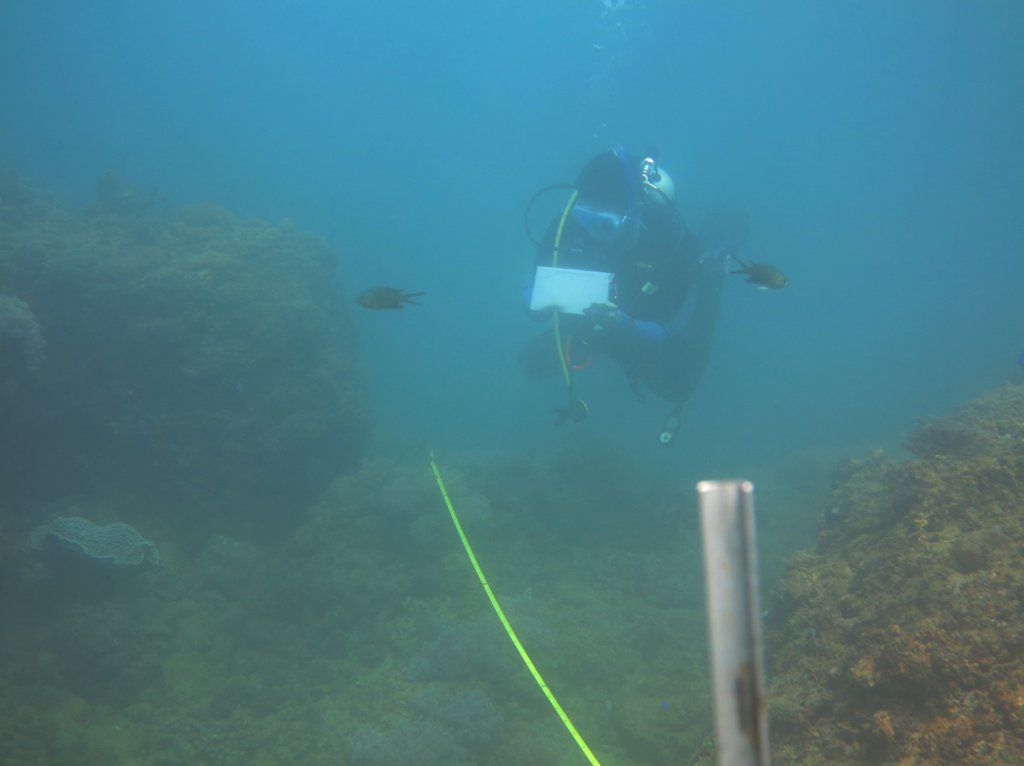

There was a lot of challenges encountered during the entire duration of the study, but out of all of them there were two that were most memorable. The first one was diving at mesophotic reefs at Abra de Ilog. This location is near a large river with numerous tributaries, and as such it was dimly lit and silty. Though I have dived in sites with similar characteristics, being 30 m underwater with these conditions was a new and kind of scary experience for me, and presented an interesting challenge to overcome. The second one was when the co-authors and I were standardizing our procedures. As this was the first major project in the Philippines that studied mesophotic reefs, we didn’t have advanced diving technologies (e.g. tech equipment, rebreathers). To compensate, we took what was an established methodology in shallow reefs (i.e. fish visual census and photoquadrat) and used those on mesophotic reefs. However, with open-circuit scuba, we were constrained by dive time, and a lot of practice was devoted to find the optimal transect tape length and dive duration where we could obtain meaningful data without endangering ourselves.

What was the most memorable moment in undertaking this study?

My most memorable experience had to be diving at Patnanungan, Quezon Province. This study site is not particularly beautiful and is essentially degraded. However, it was in this site that I was able to observe a mesophotic algae assemblage, which I have not seen anywhere else in the Philippines. At 30-35 m depths, there was a site that was dominated by species of Sargassum, which we think is related to the adjacency of the site to nearby grouper mariculture farms.

What was your favorite research site in this study and why?

My favorite dive was in Apo Reef Natural Park. Nowadays in the Philippines, there are only a handful of sites where you can see numerous corals and fishes as most sites have been degraded due to a multitude of natural and human stressors. One of the sites that have remained rather ‘untouched’ is Apo Reef. Some rare observations that were highlights of my trip there was getting to see the humphead parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum) at some of our shallow sites, and the high abundance and biomass of planktivores Thompson’s surgeofish (Acanthurus thompsoni), red-toothed triggerfish (Odonus niger) and spotted unicornfish (Naso brevirostris) at our mesophotic sites.

Other than your co-authors, with whom would you like to share credit for this work?

There are numerous people that assisted us during the work, and I think all of them deserve a fair share of the credit. The local government officials of Sablayan, Mindoro was receptive of our research and provided us with research permits and logistical support. The rangers stationed at Apo Reef were quite accommodating pertaining to our use of their compressor and scuba tanks. The laboratory assistants, dive master, boat personnel, students and other members of our research team for the assistance in the preparation and implementation of the surveys.

Any important lessons learned (through mistakes, experience or methodological advances)?

Numerous lessons were learned throughout our study, but the most memorable would have to be getting used to and following our diving procedures. Since we were not using advanced diving technologies, we made sure that when we descended to mesophotic reefs, we knew each of our roles, the dive time allowed and what to do in case of emergencies. Though all of us were accustomed to scientific diving, there is an extra net of safety that we carefully considered when diving at mesophotic reefs due to the added hazards.

Can we expect any follow-up on this work?

Yes, we are planning follow-up studies on our work, but instead of focusing purely on the composition of fish species assemblages, we are planning to expand our research to understanding ecological processes (e.g. herbivory and predation) and connectivity of fish populations at shallow and mesophotic reefs.

Featured article:

|

|

Spatial variability in reef‐fish assemblages in shallow and upper mesophotic coral ecosystems in the Philippines | article Quimpo TJR, Cabaitan PC, Olavides RDD, Dumalagan Jr. EE, Munar J, Siringan FP (2018) J Fish Biol 94:17-28 |

|