Behind the science:

Novel mesophotic kelp forests in the Galápagos archipelago

2023, December 3

Posted by Veronica Radice

“Offshore mesophotic kelp forests discovered in the Galápagos”

How do you pronounce “mesophotic” – ‘mee-so’ or ‘meh-so’ -photic?

I use both. When I am in a predominantly anglophone environment, I say “mee-so” but you often switch to “meh-so” when I have been speaking Spanish, as that pronunciation matches the Spanish one.

Are you more interested in charismatic megafauna or scouring the benthos for cool creatures?

While I am all about the enigmatic life forms that inhabit the benthos, much of my work focuses on studying mesophotic kelp which I would describe as charismatic “megaflora”, as they are among the most widely known seaweeds given their large size and the majestic marine forest they form.

What was the most challenging aspect of your study (can be anything from field, lab to analysis)?

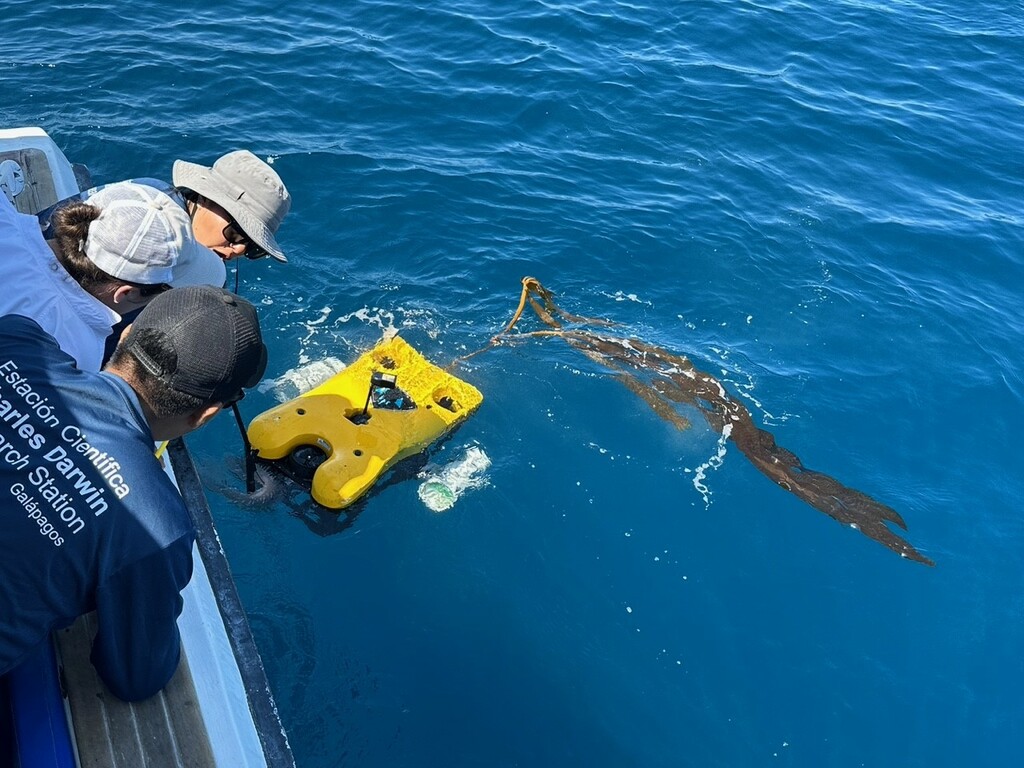

Piloting ROVs on rough sea days in Galapagos on a 7 to 12 m long speed boat can be brutal. Wind, swell and ripping surface currents make it extremely challenging to keep the boat in position while also trying to steer ROV transects along a more-or-less straight path at 50-70 m depth to generate video data usable for analysis. Not getting seasick is almost impossible while looking at wobbling real-time footage that the ROV is rendering on a laptop screen rocking with the boat’s motion.

What was the most memorable moment in undertaking this study?

The day we spied a mesophotic kelp forest covering the summit of a knoll (small seamount or underwater mountain) formed by a kelp species hitherto unknown in the region and possibly new to science.

What was your favorite research site in this study and why?

It has to be Bajo San Luis, a shallow seamount between Santa Cruz and Isabela islands in the Galapagos (south-central region of the archipelago), where we located the first novel kelp forest. The kelp population at this site is particularly dense and coexists with sea fans, black corals, and dense fish schools. We also suspect that the seamount creates advecting currents that increase the productivity of the surrounding waters, as we often witnessed fish bait balls on the sea surface pursued by tuna, seabirds and dolphins. We also encountered a mama humpback whale with her calf.

Other than your co-authors, with whom would you like to share credit for this work?

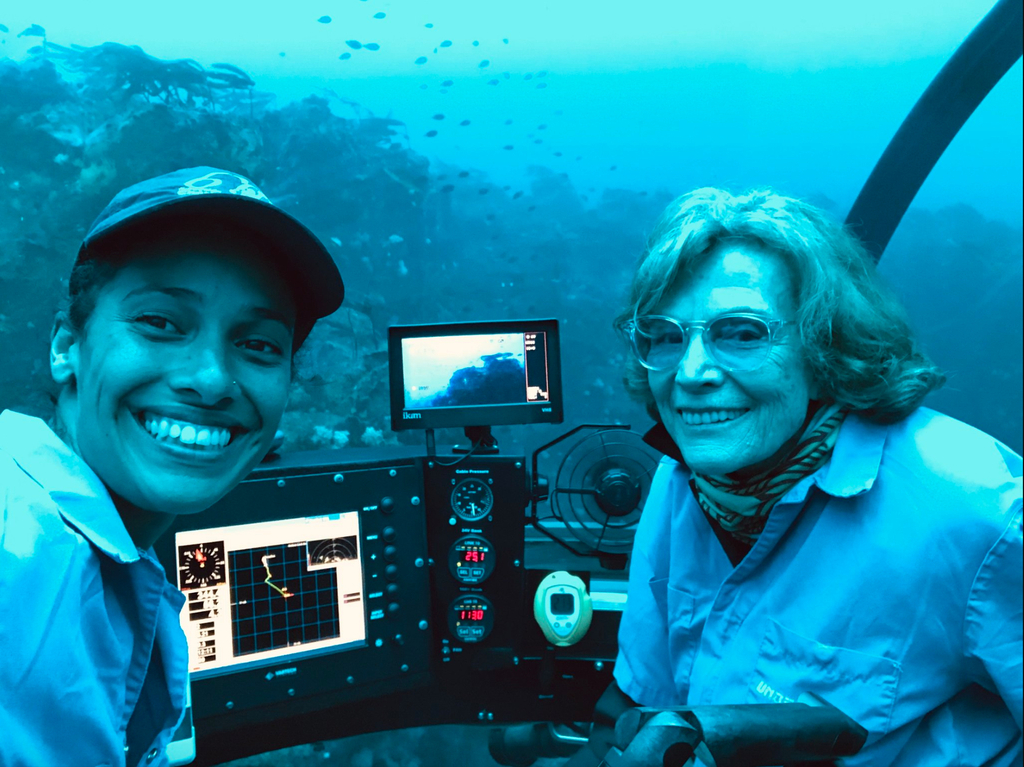

The institutions who believed in this project and supported the acquisition of permits and funding as well as ground logistics were the Charles Darwin Foundation, Galapagos National Park and National Geographic Society. Thomas Glebas, Chief Engineer at VideoRay, a ROV manufacturing company in Philadelphia, supported this project from day one, bringing his tried-and-tested ROV technology and a small team of experts to help explore uncharted mesophotic seamounts in the Galapagos. Sylvia Earle – who needs no introduction – a phycologist who helped collect many of the first macroalgae specimens in the Galapagos in the 1970s, was thrilled about our deep-water kelp discovery and supported it ever since. In 2019, and more recently 2022, she organised research cruises with manned-submersibles that helped us explore, survey and sample the deep-water kelp populations across the archipelago’s mesophotic zone.

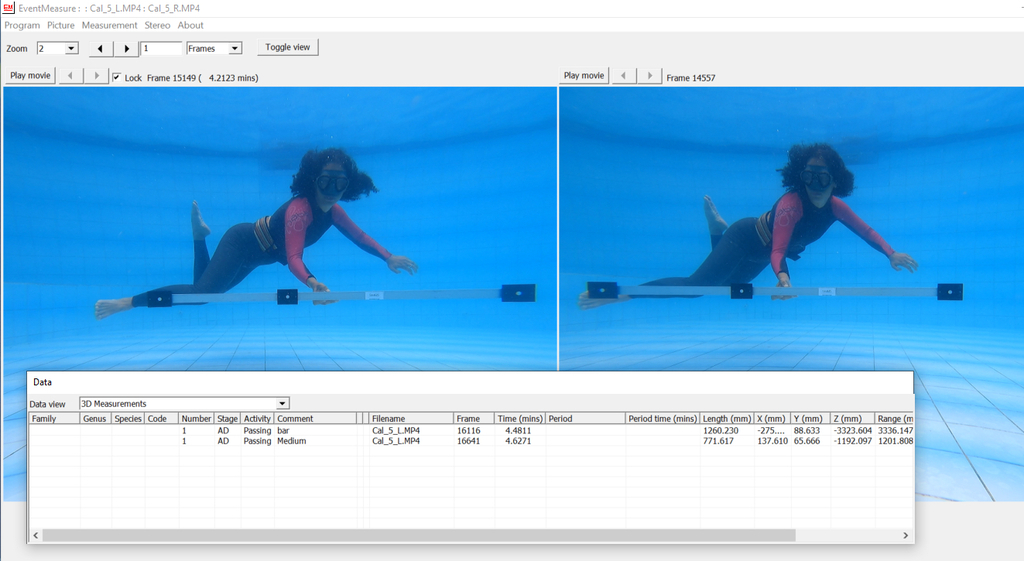

Any important lessons learned (through mistakes, experience or methodological advances)?

Learning how to pilot, troubleshoot and fix ROVs has taught me that I can be “techy” and generally upped my confidence when working with new gear and software, something I used to find very intimidating. Also, doing mesophotic research from the “surface”, which involves using many devices on long ropes or cables e.g., ROVs, Niskin water samplers, and oceanic probes, can be incredibly exhausting, as it involves lots of lifting, pulling, loud communicating (shouting) and, if unlucky, vomiting. So planning a 1-2 day break between field days has been critical. It also taught me the sooner you share your skills with others and train a solid team the more you can delegate and focus on collecting the best data possible!

Can we expect any follow-up on this work?

Yes, we are working towards understanding the seasonal changes in temperature and nutricline that occur at the mesophotic depths the kelp forests are found at. We hope to learn how these changes affect kelp forest communities in the Galapagos, and what this can tell us about their resilience and potential role as deep-water refuges in the light of marine heat waves becoming more frequent and intense.

Featured article:

|

|

Novel mesophotic kelp forests in the Galápagos archipelago | article Buglass S, Kawai H, Hanyuda T, Harvey E, Donner S, De la Rosa J, Keith I, Bermúdez JR, Altamirano M (2022) Mar Biol 169:156 |

|