Blog:

An interview with Daniel Holstein

2017, November 6

Posted by Veronica Radice

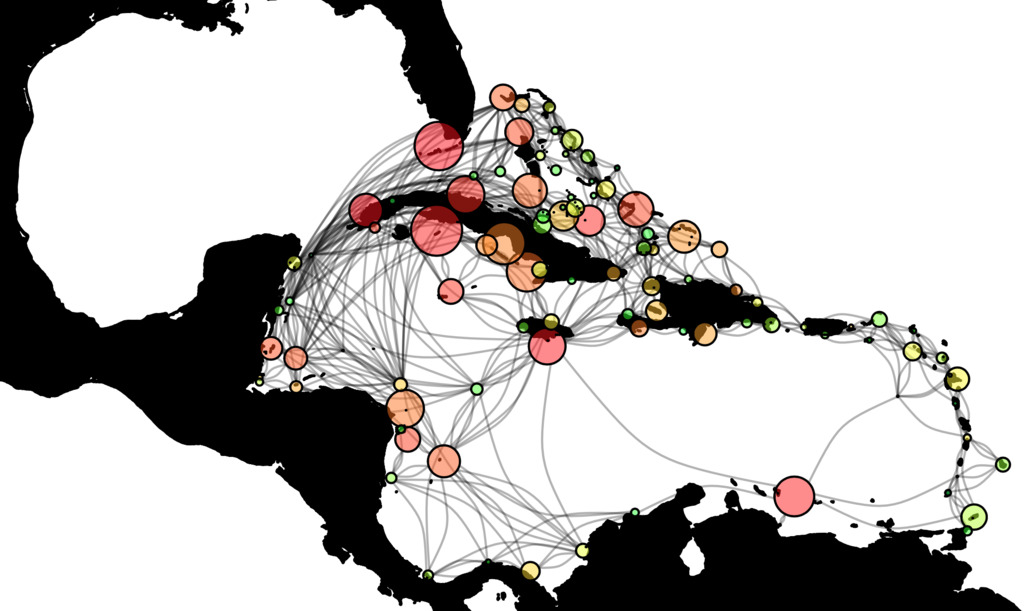

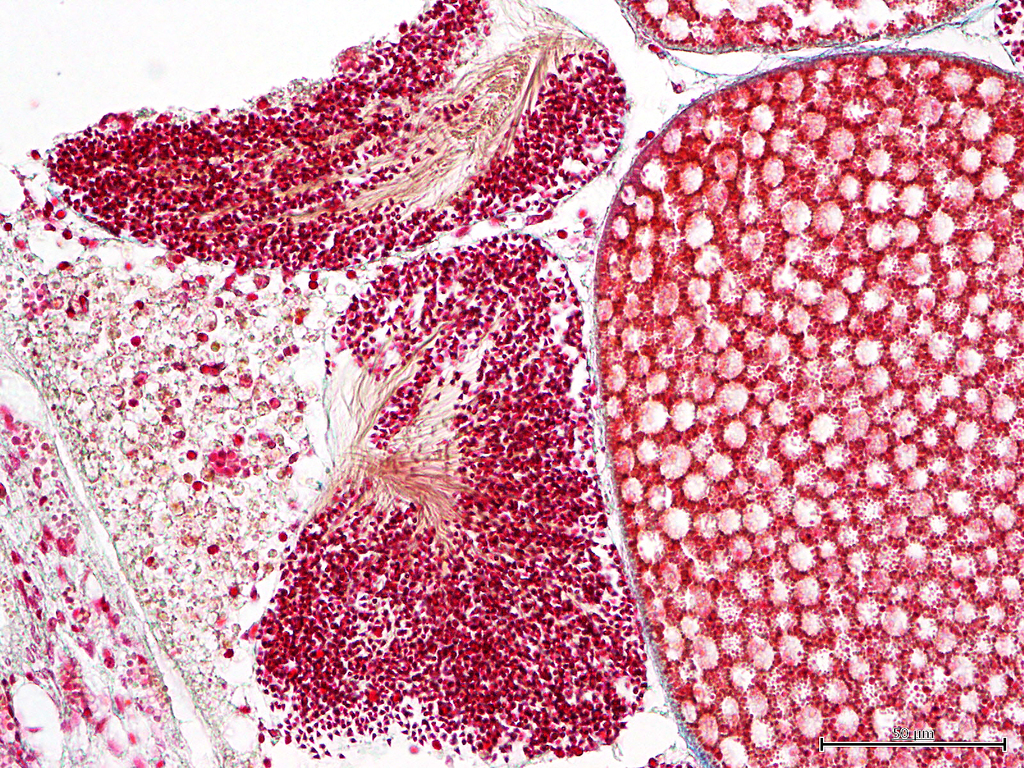

Dan is a Visiting Scholar at Duke University's Marine Lab, and in 2018 will join Louisiana State University's Department of Oceanographic and Coastal Sciences as an Assistant Professor. His research focuses on the connectivity of coral reef metapopulations, and on the resilience of marine metapopulations to perturbations and climate changes. He has continued interest in mesophotic coral ecosystems as potential refugia from climate change - and how these refuges and adjacent habitats interact through the exchange of individuals or genes to produce persistent metapopulations. Tools employed by Dan's lab include simulation and ecological modeling, coral reproductive histology, and deep genome sequencing; all aimed at deciphering the mechanisms that control reef population connectivity, and how connectivity influences persistence in time.

Early Career Scientist: Daniel Holstein

How do you pronounce “mesophotic” – ‘mee-so’ or ‘meh-so’ -photic?

As a transplant from the NE U.S. to the South, I appreciate that people can get protective of their scientific pronunciations. I say ‘meh-so’, but the ‘mee-so’s should feel no shame!

Are you more interested in charismatic megafauna or scouring the benthos for cool creatures?

I love both! As a researcher, I am most interested in what’s on the benthos, building biological communities and ecosystems. However, the ocean is home to some awe-inspiring large animals, and offers encounters with those animals that are now rare in terrestrial environments. The benthos and epipelagic megafauna are both so integral to my interests in the ocean, it’s hard to love one, and not the other. Plus, a shark encounter during deco always helps pass the time…

What is your primary research interest, and how does it link with the mesophotic zone?

My primary interest is in how metapopulations – or networks of habitats connected by migration – function. These large, complex networks change shape and behave differently when there are major environmental or biological changes – like climate change, for instance. Studying complex metapopulations can help us to understand why some species go extinct, and some persist; and how individual habitats help to determine a species’ fate. Coral reefs are dynamic, complex communities that appear to be in real trouble due to all sorts of anthropogenic and climate stressors. Some mesophotic reefs are potential refuges for some species. I’m very interested in how these protected reefs will fare during climate changes, and how migration to or from these reefs could change the shape and persistence of coral reef metapopulations in an uncertain future.

Describe the location of your main (or most interesting) study site and how it fits in with your research questions.

Most of my mesophotic work takes place in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The southern Puerto Rican Shelf supports some truly incredible upper mesophotic reefs, dominated by Orbicella spp. Considering the dramatic loss of coral cover in the shallow U.S. Virgin Islands, due to bleaching and disease, these environments are really special. We’re looking into how connected – both genetically and through larval migration – these deeper reefs are to the shallows. It’s possible that mesophotic reefs are integral to population connectivity in the region.

What is your primary means of accessing mesophotic depths to conduct your research (e.g. ROV, SCUBA, rebreather, submersible) and what were the main challenges to overcome?

For the most part I use open-circuit SCUBA with either low-mix nitrox or trimix to reach our primary dive sites, and Megalodon close-circuit rebreathers for extended or deeper dives. Getting certified to do this kind of diving can be a real challenge – but taking the time and developing a safety-first dive mentality is really important to doing the science.

What do you remember from your very first exposure to coral reef or mesophotic fieldwork?

I was fortunate to be exposed to coral reefs from a very young age, but I remember my first dive on a mesophotic reef as being truly remarkable. I had never dove below 100 ft (30 m) before, and descended to 130 ft (40 m) both fearful and excited to collect coral tissue samples. True, I may have been slightly narc’d, but I was blown away by the health of the coral and the abundance of large, surprisingly inquisitive reef fish. The reef was a treasure, buried 12 km offshore where I never would have guessed, and I was hooked on mesophotic reefs.

What new skill(s) have you learned during your research and what is one thing (skill, program, advice, etc.) that you wish you learned earlier in your science journey?

Collaboration. Mesophotic research is, by its nature, difficult and technical. During our graduate studies, we often feel vulnerable and powerless in collaborative situations, which is really a shame. Strong collaborations allow us to become multi-disciplinary researchers, and are the backbone of exploring the complexities of the mesophotic zone, or any mare incognitum. And, as always, I believe coding to be essential to success in the sciences. Whether it’s R, Matlab, Python, whatever – strengthen those muscles when you can, as you won’t have the time later in your career.

How do you keep current with an endless stream of research coming out (or any favorite science website or blogs that you follow)?

It is a constant challenge, and one in which I have room for improvement. I use Google Scholar Alerts to keep me apprised of papers with keywords of interest. Social media, like Twitter and Facebook let me track the research of colleagues or in research communities I follow. Papers are accumulating exponentially – I use Mendeley to keep my head straight, and my references organized – but I am consistently caught off guard with information I’ve missed. Never underestimate the power of communication among colleagues; I consider emails from colleagues one of my most important sources of otherwise overlooked papers.