Blog:

An interview with Michael Studivan

2017, October 23

Posted by Veronica Radice

Michael is an Assistant Scientist at the University of Miami's Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS) and NOAA's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML), as part of the ACCRETE program. His research involves the use of advanced molecular techniques to better understand genetic connectivity of coral ecosystems and physiology/adaptation of corals. He is a technical diver with certifications from GUE, AAUS, TDI, PADI, and PSI/PCI. He also has ten years of video editing experience and has produced outreach videos for his projects.

Early Career Scientist: Michael Studivan

How do you pronounce “mesophotic” – ‘mee-so’ or ‘meh-so’ -photic?

I am a recovering ‘mee-so.’ I know it’s ‘meh-so,’ but old habits die hard!

Are you more interested in charismatic megafauna or scouring the benthos for cool creatures?

My favorite experiences as a diver have been from finding cool inverts in some crevice on the bottom. There’s something about experiencing the tiniest details to remind you how intricate and complex the world can be. Anyone can see a whale shark, but catching a bristle worm spawning within the minute you are watching? Possibly the coolest thing I have seen underwater.

What is your primary research interest, and how does it link with the mesophotic zone?

There is a theory that mesophotic reefs may serve as population refugia for threatened shallow reefs. This collection of hypotheses, termed the Deep Reef Refugia Hypothesis, assumes that populations are connected across depths, and that depth-generalist conspecifics are successful in both environments. My research seeks to answer these questions using a model coral species across the Gulf of Mexico. I am using population genetics to describe broad-scale connectivity, and gene expression profiling and skeletal morphometrics to understand whether shallow and mesophotic corals demonstrate specific adaptations to their different environments. Once we have a better understanding of population connectivity through time and the ability of an individual to survive in shallow and mesophotic conditions, we can start to address questions of reef services and ecological connectivity that underlie the DRRH.

Describe the location of your main (or most interesting) study site and how it fits in with your research questions.

While I have enjoyed all of my research sites, nothing has compared to the awe-inspiring mesophotic reefs of the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary (FGBNMS). Lying 180 km off the coast of Galveston, Texas, this oasis-like reef system is considered high-latitude and spatially isolated, yet boasts some of the highest coral cover in the Caribbean. Given the relative persistence of the healthy reefs at FGB, we suspect the region (especially mesophotic habitats) to be an important source of coral larvae for downstream reefs in the Gulf of Mexico and Florida. Aside from the massively-terraced mesophotic coral colonies found at FGB, it is one of the few reefs that you could possibly see whale sharks, manta rays, and the friendliest large groupers in a single dive.

What is your primary means of accessing mesophotic depths to conduct your research (e.g. ROV, SCUBA, rebreather, submersible) and what were the main challenges to overcome?

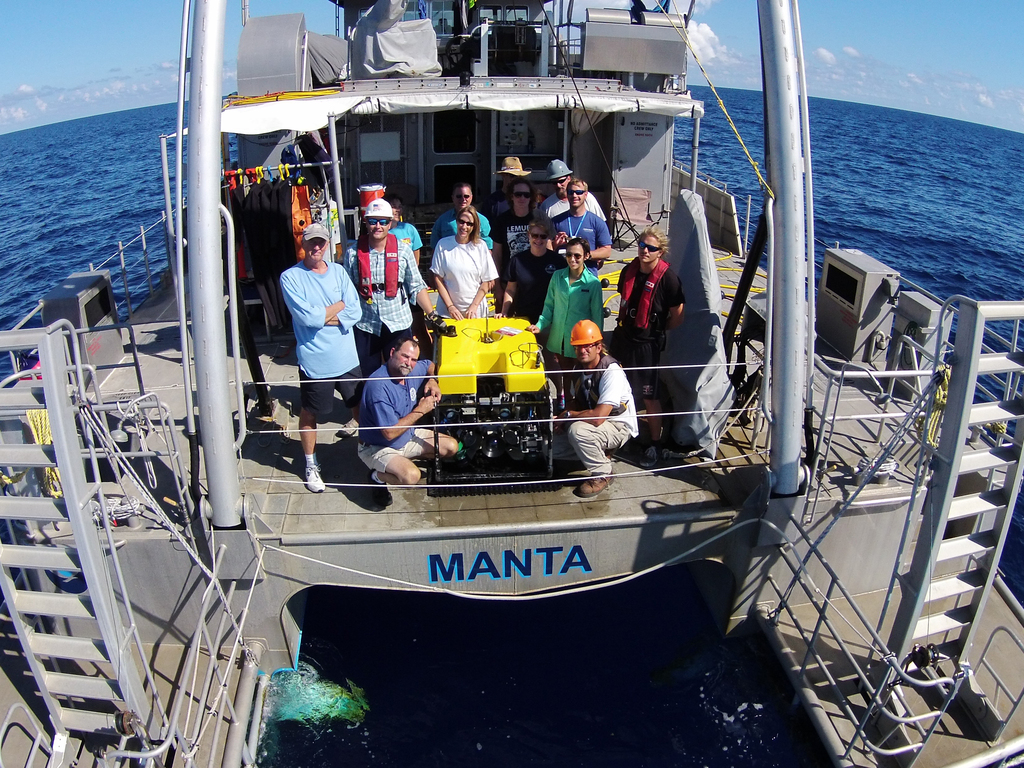

For exploration and characterization of mesophotic habitats, we primarily use remotely-operated vehicles (ROVs) to maximize time underwater and extend depth capabilities. Collection of coral samples for my dissertation research, on the other hand, was done almost exclusively with SCUBA and rebreather divers as they are much more efficient with sampling. To compare methods, collection of a single coral fragment takes about two minutes with a diver, and fifteen with the ROV sampling toolsled. Plus, you can be a lot more delicate while handling samples to preserve the skeleton than with stainless steel manipulator jaws. Our biggest challenge in conducting diving and ROV ops at isolated mesophotic reefs has been weather. Conditions in the Gulf of Mexico are extremely unpredictable, and quickly building seas and oncoming hurricanes have cut short several of our expeditions.

What do you remember from your very first exposure to coral reef or mesophotic fieldwork?

My earliest fieldwork with mesophotic reefs involved the exploration of coral habitats along the continental shelf of the northwest Gulf of Mexico. While I was blown away by the diversity of benthic life, it wasn’t until my first technical diving mission that I truly came to appreciate how amazing mesophotic ecosystems are. Even with scaling lasers, watching an ROV feed on a blued-out TV monitor does not give the best spatial reference and tends to wash out the colors. Being underwater changes your perception immediately; sheets of plating corals reveal themselves to be over a meter in diameter, and fluorescent corals and fish are everywhere!

What new skill(s) have you learned during your research and what is one thing (skill, program, advice, etc.) that you wish you learned earlier in your science journey?

I think my biggest developments as a student have been with bioinformatics and social media, especially film outreach. Both skills are time-consuming and at times frustrating, but consistent dedication and willingness to learn will help you out in the long run. My advice is to start early – attend workshops, learn from the experts in your field, and don’t be afraid to ask questions! Develop your passions in ways that complement your academic strengths.

How do you keep current with an endless stream of research coming out (or any favorite science website or blogs that you follow)?

On a daily basis, Twitter is my go-to. Rapid fire social media platforms are breaking the mold of how new research is disseminated within the science field and spread to the general public. Perhaps the best example of this is the release and spread of pre-print manuscripts, which have introduced me to interesting new studies I may not have seen otherwise. Looking for more in-depth coverage? Subscribe to podcasts! There are so many available covering all kinds of topics. My favorites are “How Stuff Works,” “Stuff You Should Know,” and NPR’s “TED Radio Hour” and “Invisibilia.”