Behind the science:

Population connectivity among shallow and mesophotic Montastraea ca...

2018, September 27

Posted by Veronica Radice

Fields

Connectivity

Molecular ecology

Focusgroups

Scleractinia (Hard Corals)

Locations

Belize

USA - Gulf of Mexico

USA - Pulley Ridge

Platforms

Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV)

SCUBA (open-circuit or unspecified)

“Coral population connectivity reveals potential for refugia in Gulf of Mexico”

What was the most challenging aspect of your study (can be anything from field, lab to analysis)?

Field work in the Gulf of Mexico is always a massive undertaking due to the relative remoteness of MCEs and the resources required to explore them. It’s not always easy to complete sampling objectives when we’re being chased by hurricanes, battered by 2 meter seas, or faced with equipment malfunctions >100 km from shore. But these challenges make the times when things go according to plan feel that much more rewarding.

What was the most memorable moment in undertaking this study?

Given the amount of work needed to be accomplished per dive and the logistical challenges associated with mesophotic sampling, we often don’t get much time to enjoy the environments we’re studying. However, decompression stops offer a unique opportunity to slow down and look at the reef and to reflect on the biological complexity of MCEs. Perhaps most fitting, my most memorable moments are from unexpected visits by pods of dolphins, huge schools of jacks, manta rays, and whale sharks during our mid-water stops. It is then that I truly appreciate the idea that MCEs in the Gulf of Mexico are “oases” in the middle of otherwise sparse habitats and are very important to community function and connectivity throughout the region.

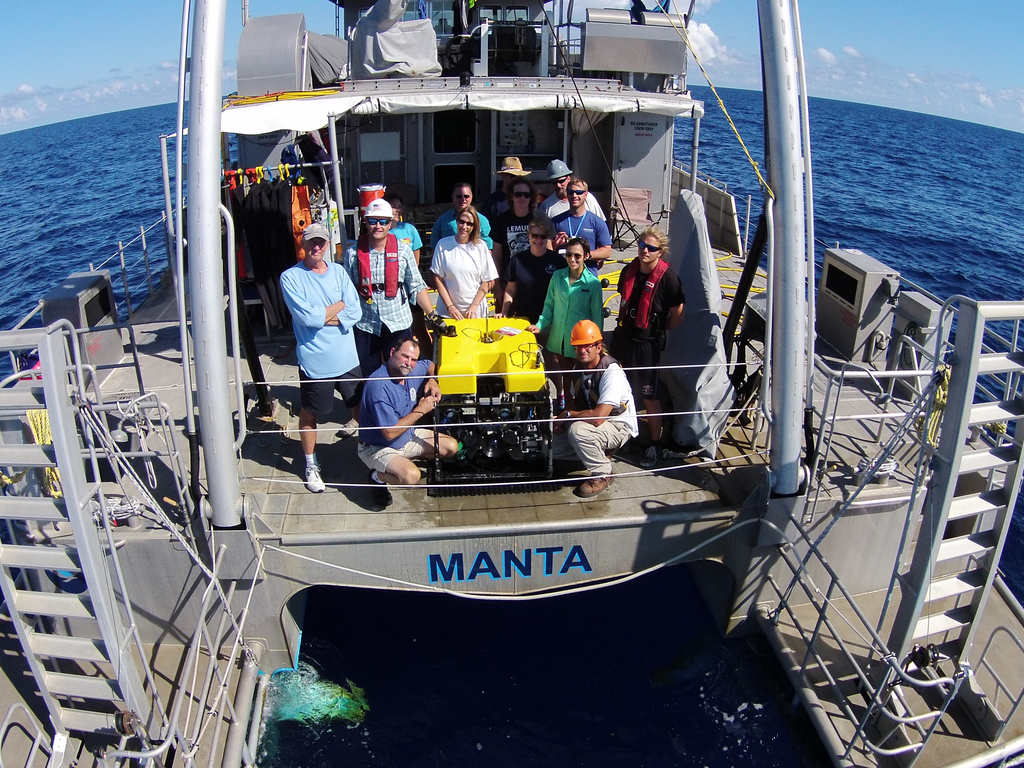

To explore MCEs in Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary (FGBNMS), we assembled a team of species experts from FAU Harbor Branch and FGBNMS, and the UNCW UVP to pilot their Mohawk ROV. Data from these missions supports habitat protection in the region.

(C) Voss Lab, FAU Harbor Branch

[CC BY-NC 4.0]

To explore MCEs in Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary (FGBNMS), we assembled a team of species experts from FAU Harbor Branch and FGBNMS, and the UNCW UVP to pilot their Mohawk ROV. Data from these missions supports habitat protection in the region.

(C) Voss Lab, FAU Harbor Branch

[CC BY-NC 4.0]

What was your favorite research site in this study and why?

Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary (FGBNMS) is hands down my favorite place to dive (or explore via ROV!). Being 180 km off the Texas coast in the Gulf of Mexico, it really is an isolated, high-latitude reef system, but it has some of the most pristine coral reef habitat in the Tropical Western Atlantic. Many of the coral colonies are taller than me, and the reef habitat continues from a relatively shallow coral cap at 17 m down to the mesophotic bank margin at 55 m. The fish and invertebrate occupants are equally large, and FGBNMS is frequented by turtles, manta rays, whale sharks, and exceptionally friendly groupers. If I’m not doing FGBNMS proper justice in text, check out these two videos from our most recent expedition, where we used scooters to film video across the mesophotic bank margins to the top of the reef slope (carbonate caps). Video 1 here and Video 2 here.

Other than your co-authors, with whom would you like to share credit for this work?

This study would not have been possible without massive support from many partners and collaborators throughout the planning and execution phases of the research. Specifically, we would like to thank G.P. Schmahl, Emma Hickerson, Marissa Nuttall, and Michelle Johnston of FGBNMS; Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary; the crews of the R/V Manta, R/V Walton Smith, and M/V Spree; Lance Horn and Jason White from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington Undersea Vehicle Program; and Zach Foltz and Scott Jones from the Smithsonian Marine Station. We had many divers participate in our sampling expeditions including: Jeff Beal, Jake Emmert, Rachel Susen, Chris Ledford, Ryan Eckert, Jennifer Polinski, Amanda Alker, Danielle Dodge, Alycia Shatters, Patrick Gardner, John Reed, Mike McCallister, Matt Ajemian, Robbie Christian, Rick Gomez, Evan Tuohy, Milton Carlo, Mike Echevarria, Michael Terrell, Casey Coy, John Embesi, and Mike Dickson. Greg O’Corry-Crowe and Tatiana Ferrer contributed to data collection in the lab with capillary electrophoresis, and Andrew Baker and Xaymara Serrano provided additional data and troubleshooting assistance.

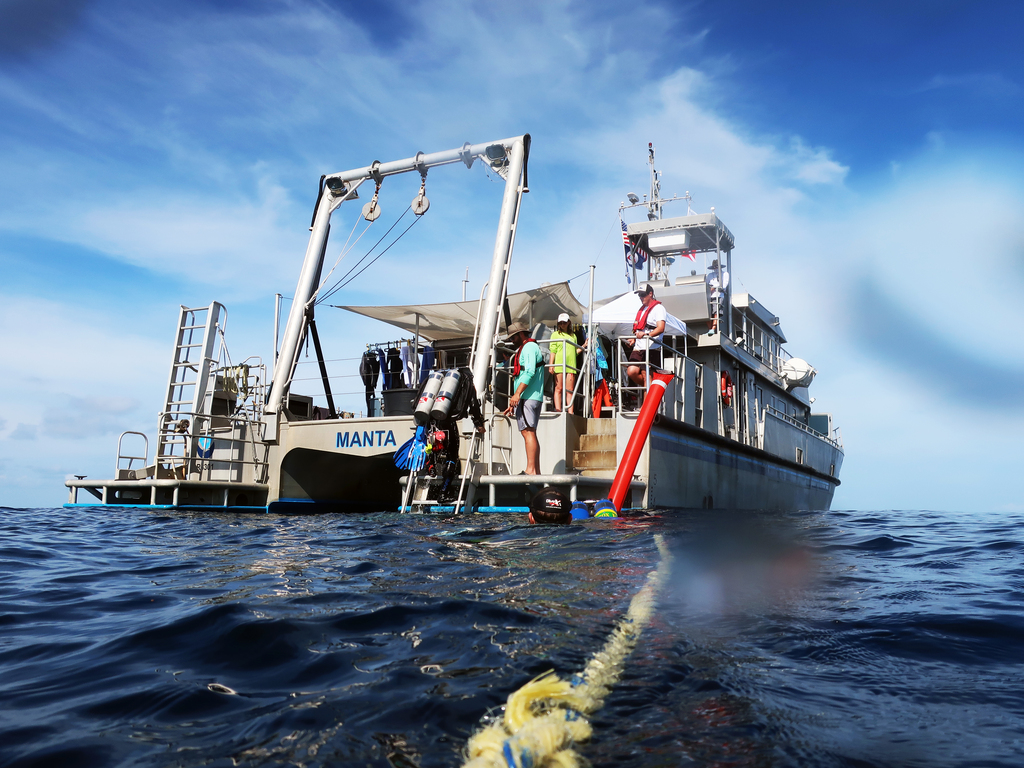

On a calm day, technical divers can take their time to get back on board the RV Manta after an 80 min dive to 50 m.

(C) Jeff Beal, FWC

On a calm day, technical divers can take their time to get back on board the RV Manta after an 80 min dive to 50 m.

(C) Jeff Beal, FWC

Voss Lab graduate student Ryan Eckert descends along the vertical wall down to 35 m near Carrie Bow Cay, Belize.

(C) Voss Lab, FAU Harbor Branch

[CC BY-NC 4.0]

Voss Lab graduate student Ryan Eckert descends along the vertical wall down to 35 m near Carrie Bow Cay, Belize.

(C) Voss Lab, FAU Harbor Branch

[CC BY-NC 4.0]

Any important lessons learned (through mistakes, experience or methodological advances)?

Always take pictures of your corals pre- and post-sampling! When you have to repeatedly sample a site over multiple years, it becomes very easy to accidentally resample the same coral colony. For population genetics analyses, it then becomes difficult to identify clonal genotypes as true clones or duplicate samples without a photo reference. This was especially important for this study, as we identified some clones due to accidental resampling, but a large proportion of clonal genotypes that we believe are the result of increased asexual reproduction or colony fragmentation at Pulley Ridge in the southeast Gulf of Mexico. The ability to identify true clones has profound implications for the interpretation of overall population connectivity and reproductive strategies for a region.

Can we expect any follow-up on this work?

Yes! Through a collaboration with Santiago Herrera (Lehigh University), NOAA, and many other colleagues, we are expanding the geographic scope of sites in the NWGOM and adding population genetics analyses of other species to better represent different taxa and life history characteristics. Additionally, we are making the jump from microsatellites to next-generation sequencing approaches for increased resolution. Additionally, the data from this study are contributing to an ongoing proposal by the FGBNMS Sanctuary Advisory Council to expand the FGBNMS boundaries to include 15 additional banks under NMS protection. To learn more about the sanctuary expansion and for updates regarding the legislation, visit the FGBNMS website.

Aerial view of the Smithsonian field station on Carrie Bow Cay, with the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef seen in the background. MCEs in Belize appear to be larval sources for coral reefs in the southeast Gulf of Mexico.

(C) Voss Lab, FAU Harbor Branch

[CC BY-NC 4.0]

Aerial view of the Smithsonian field station on Carrie Bow Cay, with the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef seen in the background. MCEs in Belize appear to be larval sources for coral reefs in the southeast Gulf of Mexico.

(C) Voss Lab, FAU Harbor Branch

[CC BY-NC 4.0]

Featured article:

|

|

Population connectivity among shallow and mesophotic Montastraea cavernosa corals in the Gulf of Mexico identifies potential for refugia | article Studivan MS, Voss JD (2018) Coral Reefs |

|